A few days ago, I was walking home and passed by a bush of white flowers in full bloom. They looked pretty spectacular lit by the afternoon sun. On taking a closer look, I realized that what I thought were flowers were actually flower bunches, each of them made up of hundreds of tiny flowers. And on each bunch, there was a single honeybee zipping about from flower to flower.

Watching these bees through my camera lens, I could see something quite interesting. As they landed on the flowers, they would kick up grains of pollen that would rise up like dust. And then the bees would do something quite odd – they would fiddle with their knees. I zoomed in to see what was going on.

There’s something quite peculiar about this photograph. What’s that fleshy appendage stuck to the knees of the honeybee? It looks, to me, somewhat like a human ear. And even stranger – the bees don’t have it when they arrive on the flower. But in a few minutes this thing begins to grow, and in about 15 minutes it’s as engorged as you see in the picture.

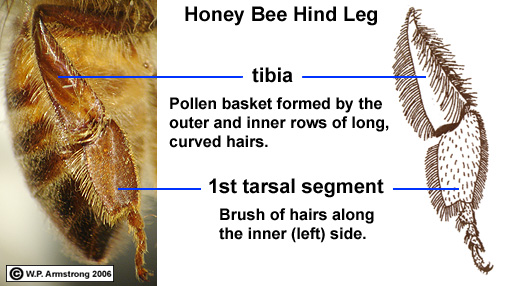

In addition to collecting nectar from flowers, honey bees also collect pollen. And what you’re seeing in these photographs is an incredible adaptation that helps bees go about their business of collection. It’s called a pollen basket, and here is how it works.

Bees are hairy creatures, and they get covered in pollen. They rake themselves clean with combs that are built into the inner surfaces of their hind legs. Next, they move all this collected pollen to a joint between the segments of their legs – their knees. This joint functions as a pollen press, and it squeezes the pollen into handy little pellets. But these pellets need to be stored somehow. And so, here is the next adaptation. The outer surface of the hind leg is concave, and it is covered in many small hairs. It’s a basket! This is where the bees store these compressed pollen pellets, and that’s what you see in the above picture. The basket is actually transparent, and so the fleshy color in the pictures above is the color of pollen.

The weird thing about this is that the basket is open at the bottom. So why doesn’t the pollen fall out? That’s because there’s a single strong hair that prevents this from happening, which functions as the lid of the basket.

Although I couldn’t quite make out the details, watching this elaborate packing process through the zoom lens was quite mesmerizing and I was merrily snapping away. The bees didn’t seem to notice me at all, but I realized that I was getting odd looks from my neighbors, so I decided it was time to take my leave.