There are few pleasures in life that exceed the simple joy of devouring home-cooked pancakes on a Sunday afternoon. I’m not much of a cook, but brunch is by far my favorite meal. So I decided that it’s time to take matters into my own hands, and improve my pancake making skills. Oddly enough, the first job I ever had as a college freshman was as a breakfast chef in my dorm. Back then, I’d make pancakes from a box, using Aunt Jemima’s pancake mix. I’ve since realized that it’s not much harder to make pancakes from scratch, and it’s a whole lot more gratifying. The quest for the perfect pancake is something of a lifelong journey. But unlike other boring journeys, this one is delicious, and served with syrup. Mmmm.

So where do we begin? I favor buttermilk pancakes myself, for their light and fluffy texture. If you go online and look for recipes, you’ll find plenty that claim to be the BEST buttermilk pancakes. Are these recipes really all that different? What sets them apart? And what’s the essence of a truly excellent buttermilk pancake?

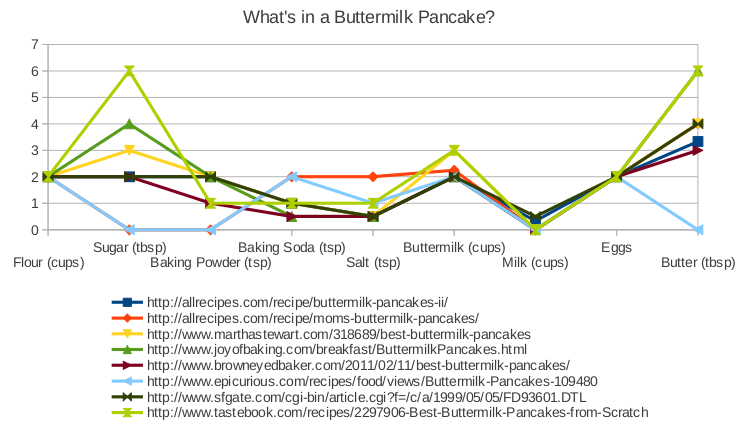

Like any scientist worth their salt (sorry), I decided to answer this question with a graph. After all, the whole is just the interaction of its parts. So let’s take apart what the web thinks of as the perfect pancake.

Above, I plotted the ingredients that go into a buttermilk pancake, according to eight highly rated online recipes. I normalized the recipes so that they all have the same amount of flour. You’ll see that there are certain essentials that you just don’t mess with. You definitely need one egg for every cup of flour. And there isn’t much variation in how much salt or baking soda you put in. On the other hand, these recipes vary widely in how much butter or sugar they include. Presumably, the excellence of a pancake is less sensitive to variations in these other ingredients. But which recipe do you follow? What’s a good empiricist to do?

I decided to take the average of these recipes, and build a pancake that strikes a balance between the excesses of its online progenitors. In so doing, I’m following the idea behind Jeff Porter’s ‘Eigen Pancakes’, from Cooking for Geeks.

So here are the ingredients for my eigen-pancakes. The quantities turned out fairly close to this trustworthy recipe from Serious Eats. And it tastes pretty darn good. But don’t take my word for it, try it out yourself.

Dry ingredients:

- 2 cups flour

- 2 tablespoons of sugar

- 1 teaspoon baking soda

- 1 teaspoon baking powder

- 1 teaspoon salt

Wet ingredients:

- 2 cups buttermilk

- 2 eggs

- 4 tablespoons of butter (melted)

And here’s the recipe:

- Combine the dry ingredients in a large bowl.

- In a separate bowl, whisk together the wet ingredients

- Pre-heat a griddle over medium heat. If you flick water onto the surface and it sizzles, it’s ready.

- Pour the wet ingredients into the dry mix. Stir until just combined. There should be lumps in the mixture. Resist the temptation to over stir.

- Butter the pan very lightly, and scoop the batter on to the griddle. Once bubbles form, carefully flip the pancakes. Cook until golden brown.

With a little practice, this recipe makes a reliably delicious stack of pancakes.

I like playing with my food, and prodding beneath the surface. One aspect of cooking that’s always bothered me is the seeming arbitrariness of recipes. What do the various ingredients do, and why do we need them all? In a way, every recipe hides a story of reactions that create new flavors and textures.

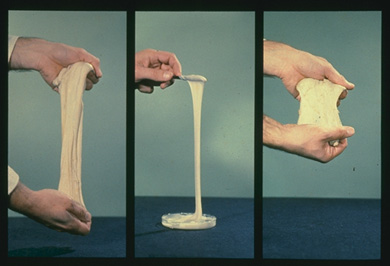

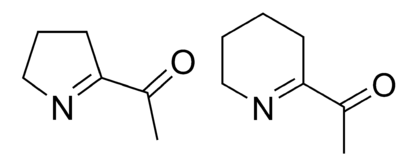

So here’s the science behind your breakfast. A pancake is the result of a pretty incredible transformation. The magic begins when you mix the flour with the wet stuff. If you look through a microscope, flour contains two different kinds of proteins called glutenin and gliadin. When moistened and mixed, these proteins link together to form a sticky molecular mesh known as gluten. Next, you need to add a leavening agent. This is something that fills the gluten with air. Without it, leavened breads like cakes, muffins and loaves of breads would be pretty inedible.

Traditionally, people used biological agents like yeast for this purpose. The yeast munches on sugars, and excretes carbon dioxide, making thousands of little air pockets in the gluten. Put the dough in the oven, and these air pockets expand. The gluten transforms from a gooey, sticky mess into a dry and spongy substance that we call bread.

But yeast is slow to act, and so we rely on a quick chemical reaction instead. Baking soda is really an alkaline powder called sodium bicarbonate – it’s a base. Buttermilk is acidic (hence the sour, tart taste). Mix the two together, and the laws of high school chemistry tell you that you’re going to get salt, water and carbon dioxide gas. These are the bubbles that rise up as you stir the batter. You’ll want to quickly cook your pancakes, so as not to lose these precious bubbles.

This reactions works because buttermilk is acidic. Regular milk isn’t. So if you were making pancakes with milk, you’d want to use baking powder instead, which is baking soda with a powdered acid in the mix. When dry, the mixture is completely inert. Add water, and the two compounds react to give out bubbles. No acid necessary.

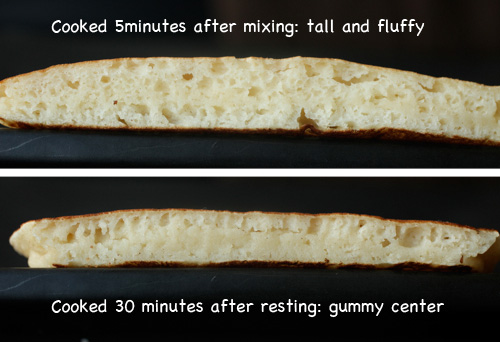

Modern baking powders are double acting, which means they give out a second round of bubbles when heated, thanks to an additional acid that is activated by heating. This helps the overworked chef, because you don’t have to cook the batter immediately after mixing. It also makes for fluffier bread. But it’s not a good idea to rely on the second round of bubbles. You can see why in this picture.

Now comes the most complex and interesting part of the process. This is the Maillard Reaction, and it’s the step that gives pancakes their aroma, and that gorgeous golden brown colour. When you raise the heat on your pancake mix, the amino acids that make up the proteins begin to chemically bond with carbon and oxygen atoms from sugars. The end result is a complex brew of hundreds of different aromatic flavor inducing molecules, that give your food a distinctive and rich palette of flavors. The Maillard reaction is behind the bold flavor of roasted coffee, the malty flavor of certain beers and malt whiskey, that brown crust on a perfectly cooked steak, the nutty notes of maple syrup, or the delightful aroma of freshly baked bread.

What’s more, the Maillard Reaction works best in an alkaline environment (i.e. a less acidic one). So the secret to getting that golden brown color is to add more baking soda. Once you’ve added enough to neutralize the acidity of the buttermilk, anything left over will add to the browning.

That sounds a little weird – how can a totally white powder help a pancake turn brown? See for yourself. Here are five batches of pancakes made with a cup of flour and all the usual ingredients, including baking powder as a leavening agent. They’re identical, except for one tiny difference. The pancake on the left has no baking soda. Every successive pancake has 1/8th of a teaspoon more baking soda, all the way up to a full half teaspoon on the right. Seems like a small change, but take a look at the effect.

In the words of J. Kenji Lopez-Alt, a MIT graduate and chef who conducted this experiment:

The pancake all the way on the left is inordinately acidic, due to the un-neutralized buttermilk. It cooked up pale and bland. It was also under-risen with a flat, dense texture. The one all the way on the right, with a full half teaspoon of baking powder had the opposite problem. It browned far too quickly, lending it an acrid burnt flavor tinged with the soapy chemical aftertaste of unneutralized baking soda. Interestingly enough, this pancake was also flat and dense—the inordinate amount of baking soda reacts too violently when mixed into the batter. The carbon dioxide bubbles inflate too rapidly, and like an overfilled balloon, the pancake “pops,” becoming dense and flaccid as it cooks.

The best pancake was the one right in the center with 1/4 teaspoon of baking soda. It cooked to a beautiful golden brown with a tender, well-risen crumb and had a clean buttermilk flavor.

And there you have it, science being put to use to answer one of the big questions in life: what’s for breakfast?

Buttermilk Pancake References:

I learnt all my pancake science from this excellent writeup by J. Kenji Lopez-Alt at Serious Eats. Here’s the recipe to go along with it.

I also enjoyed this post by Carolyn Tepolt, a Biology PhD student at Stanford who blogs about food science.

And this post by sprinklefingers is quite interesting and has some helpful tips.